Birthright: A South Carolina Adoptee’s Long Road to Identity Restoration

Adoption. The word has been in my ears since I first breathed air. And while I was in her womb, my mother's dread crossed into my veins and has remained, a pit in my stomach, all my life. The childless couple from New York City who was stationed at Shaw Air Force Base, Sumter, South Carolina applied to Catholic Charities in late fall of 1951, hoping to have a child in their tiny apartment by Christmas. In February, they got the letter: Baby Ruth Ann would be waiting in Philip's Mercy Hospital Infant Annex. They wasted no time driving north to Rock Hill to meet the five-month-old and the hospital director and Guardian ad litem, Sister Mathias.

The probation period ended in October. Sister was present for the infant petitioner, Ruth Ann, in the York County adoption court, but not the couple. So it was ordered: My identity was replaced; my name changed to Mary Ellen. Adoptee rights advocates say it matters that infants' names and identities are erased and sealed from them, and work to remedy this injustice.

My adoptive parents were content to believe I was born in Rock Hill. Why would they doubt the authenticity of the Certificate of Birth and Baptism--the word of the Church? I would learn many years later it was a stand-in for my Original Birth Certificate; a nod to my renaming and my parents’ permanent custody. They never returned to Rock Hill, nor were my adoptive father's brother and sister, my Godparents, in the Church of Saint Anne where my baptism may or may not have been.

The tiny neighborhood church served the lay brothers of St. Philip Neri's Oratory Mission, Sisters of Saint Francis of Peoria, the owners and operators of St. Philip's Mercy Hospital and Infant Home, and the working-class parishioners, and also served the purpose of the State. The court-typed carbon copy transcript on onionskin, bound by a staple to a blue legal cover, and my baptismal certificate both claim title to the infant, Mary Ellen, by priest's and parents' signatures, the grace of God, and South Carolina Law.

From what I have read in the letters my parents saved, the warranty was still effective through my early childhood. My mother was competent, a highly trained New York Public Health nurse, but she was crippled with "nerves" and misgivings; burdened by loss, and grief for the child she couldn't have. She had difficulty mothering a child not biologically her own. She claimed, when I was older but didn’t quite understand, that she had been sure I'd be taken away. Over the years, she blamed her unhappiness on Ohio but didn’t tell me about the counseling and medication.

My dad’s absences began during World War II while they were engaged. When stationed in South Carolina, he was sent to Alabama for months of training, then assigned to teach Reserve Officers training school at Ohio University. While we were in our first Ohio apartment, she pined for her mother in New York, and when he was sent back to Alabama to complete the course, she flew east with me.

They wanted to know: Is there something wrong with this child? Her refusal to eat, her willfulness? Might the mother's problems be about the child's flaws? The child psychologist assessed me at two years old. The remedy might have to be to remove me and place me in the institution with which the doctor was affiliated. But the result was: An intelligent, challenging child. This relieved my father and made him proud that I could achieve the way he did. But since he was away a good deal of the time, it was up to my mother to adjust.

That my natural mother had given me up was reason enough for them to write her off. Had they known anything of her, they'd have surely been smug. Of course, it was for the best she relinquished me. They referred to her obliquely. When they told me later that I didn’t work to my God-given potential, what did that mean? I'd learn many years later that the agency told them my birth mother lacked education due more to circumstances than ability. She was English-Irish, which suited my adoptive father--his lines were Irish—and his buttons must have burst with pride to hear, "She looks like you, Al!" I was content with it, but he didn't tell me how he knew. Now I know I'm mostly Scottish. Does our heritage matter? Adoptees say they do, and that our true origins should not be masked.

At about the half-year mark, we moved to another apartment, and Mom and I flew to New York to be with her mother a couple of times during the year we lived in Ohio. After nursery school, we left Ohio for the last time while my father finished up at the University. He bought a family home in New Jersey in the spring of 1954 and moved us in. His next assignment was a year at the N.A.T.O. base in Iceland as Aide de camp for the general.

It was a happy, comfortable year for me with ballet, kindergarten, Nana's kitchen and garden, and my neighborhood friends. If only we could have stayed there. My father wanted to make us happy, but the military made our New Jersey home life temporary. Before I turned six, he was reassigned to Victoria, Texas, and my long curls were cut off for the heat. I was keenly aware of the loss, and that family separation would be the norm. Mom and I felt the tug deeply during first grade, while he was in Tokyo.

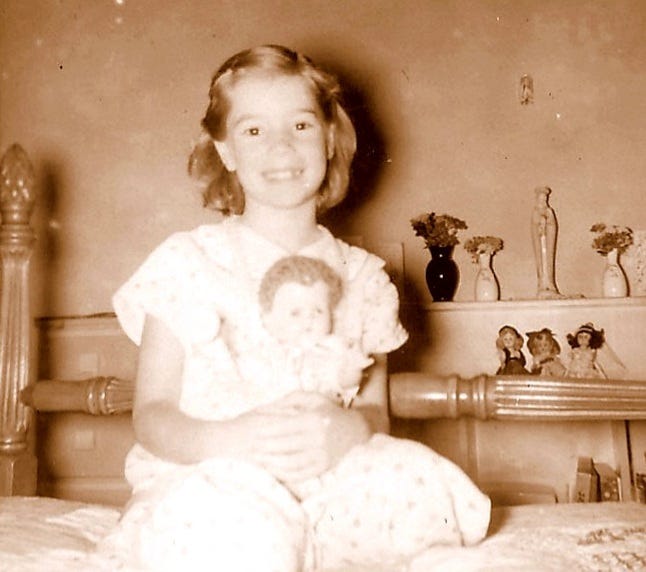

Not long before my First Communion, Dad was home with us in our Texas brick rental ranch duplex. He framed a bedtime story as a fairytale of good fortune. I knelt on the chenille coverlet with my baby doll, both of us dressed in matching flannel pajamas that Mom sewed. Dad stood near the head of my maple four-poster bed, and Mom stood at the foot, coyly deferring to his careful word choice.

"We gave you a home because you had nobody, and we loved you."

Someone gave me to them because the ones I came from were in an accident--I flashed on what I thought a car wreck looked like--and I would never see these lost ones. But it was ok, he was saying, because he and Mommy loved me and wanted to take care of me.

He didn't use the "A" word then, but I knew. His focus was on me, and that was important. My back to him on the bed, I played quietly with Betsy-Wetsy. I scanned my consciousness for the faceless, nameless ones who were once mine. No one was offering to put us back together again. I couldn't respond to the death of someone I couldn’t remember--the mother and family who were erased. And then it was, "Good night, God bless you and take care of you." A prayer, a secret, special, strange, and final.

I couldn't wait to tell my secret; to put my friends' sympathy to the test on the playground. They listened politely to my urgent story, but since I didn't appear worse for having been orphaned, we returned to play. It was my first taste of disenfranchised grief. Not perceived as a loss to them, it was an abstract that neither they nor I could fathom. Nonetheless, angst and sadness would play like a tape in my subconscious all my life.

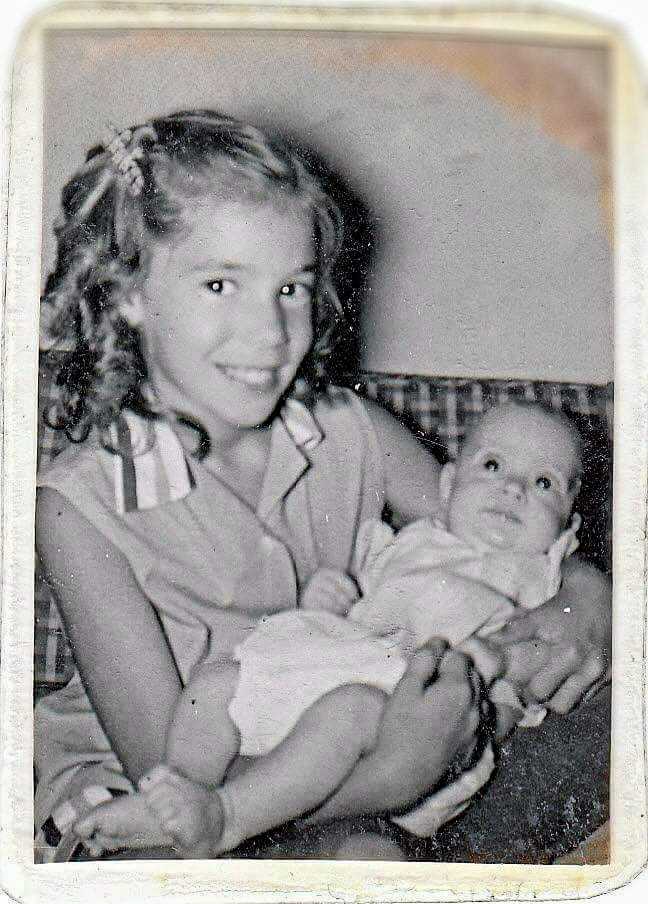

Louisiana was our next temporary state, and we would drive or fly north for Christmas and summer. Dad was in Paris for most of the second grade. When he returned, we moved on base and I changed school for third grade. That summer Mom got a call from Catholic Charities that a baby was available in Shreveport. I wasn't aware she wanted another one, but recall the excitement in our New Jersey kitchen--how excited she and Nana were for the news. I couldn't wait to tell my neighborhood friends we were getting a baby. The suitcases were soon in the trunk of our '53 Buick, and we were headed back to Louisiana to prepare for my three-month-old sister.

I remember the sweltering drive to Shreveport was a sweltering drive. We picked the baby up from the nuns—I didn't realize until many years later it was a convent home for "unwed mothers." I witnessed the formal process of a Catholic Charity's hand-over, and adoption was tangible, made flesh. I was thrilled to be the instant sister of a living doll.

Halfway through fourth grade in Louisiana, Dad got new orders. He was to leave for Langley Air Force Base, Virginia, and New York City government offices, to prepare for a three-year assignment in Japan. In our New Jersey hometown, I returned to my parochial school of kindergarten days. I happily immersed myself in fourth-grade Spanish, art, geography, and long division with the Dominican nuns, my familiar classmates, neighborhood friends, and my Nana. Mom and Dad took me to New York after Christmas to pick out a practice piano—a Baldwin Acrosonic. The strict and serious guild teacher who came to the house one evening a week would be back when we returned to the States.

Dad, an intelligence officer, was needed in post-Occupation Japan ahead of the South East Asian conflicts. We were all relaxed on our flights from Idlewild to San Francisco, and Honolulu to Tokyo, ready to embark on the new adventure. Mom would find camaraderie with other officers' wives, knowing Dad would be on temporary duty throughout East Asia more often than at our quarters. Washington Heights was the massive military housing complex we lived in for our first two years in Tokyo. In fifth and sixth grades at the sprawling private international girls' school taught by the School Sisters of Notre Dame, I made friends who might have lasted a lifetime. But like everything, they were temporary.

Life was a whirlwind and wasn't getting easier at ten and eleven. Dad was often away in the Philippines, Thailand, Taiwan, and Hong Kong. He emptied his B-4 bag’s bounties of treasures each time he returned to us. But he transformed from happy-to-be-home to unhappy disciplinarian in a flash.

To make way for the Summer Olympics, the housing complex was to be razed, and the land near Meiji Shrine, formerly the Imperial Parade grounds, was re-dedicated to the Japanese people. I loved what I had the chance to learn about Japanese culture in Tokyo, school, and Washington Heights, and was crushed to leave for Johnson Air Force Base on the outskirts. My entrance to the base co-ed junior high coincided with Kennedy's assassination. I missed my grandmother, and my anxiety was building. We didn’t talk about how going back to the States might be for me, so I didn’t know what to expect. In late June 1964, wearing a shirtwaist dress and white socks, I found myself in summer school at our New Jersey town's public high. Here I was back in the New York metropolitan area, pre-pubescent, shy, and in culture shock.

It had been several years since I heard the myth of my origins. I returned to eighth grade at Ascension School and church. On a winter Sunday afternoon after Mass and bacon and eggs, Dad gestured toward the couch and sat in his easy chair.

“You know where babies come from…”

I felt my face redden. He wasn't asking; he suspected I knew something I shouldn’t. Guilty was his default and so it was mine. With my hands in my lap, I focused on my raw, picked cuticles. The extent of my sex education was what I’d heard boys snicker about. He mumbled something, and I tensed as his voice hitched at the edge of tears.

“You know, Mary Ellen, I’m the reason your mother and I didn’t have children.”

Dread gripped me in the gut. He was unburdening his loss, transferring it to me. I wasn't to hear these facts of his life. He shouldn’t be telling me his and Mom's secret. In my shame, I fled without getting up from the couch. It wasn’t pity—what I felt was closer to revulsion.

At thirteen, I was aware of our cobbled-together family status. I often saw Dad's dissatisfaction, whether with my grades, the look on my face, or maybe, my prospects. When his point needed to be made more strongly, he used physical violence. When the person I was becoming didn't click with him. I was no longer the little child he wanted. He'd been away too often. He didn’t have the time to spend with me. To foster my studies. To keep me in line. He had migraines because of me. And I wanted to shout you're not my real father!

My self-doubt, once quiescent, now began to prickle. I wondered in the mirror: do I have brothers and sisters? Do they look like me? I was a lonely, confused teen who tried too hard to be accepted. I wasn’t guided toward higher education, although both my parents had degrees. I used smiles and friendliness to be liked by my classmates but in my mind, I was different from them. Most of them had known each other from early childhood. I was out of place, a misfit. In Holy Angels Academy, I was so wrapped up in my own head and what the girls thought of me, I had trouble thinking clearly.

It only vaguely occurred to me that South Carolina was my biological family's home state. I sometimes imagined we would meet in a local department store. Where are the others? I was secretive, hiding the turmoil until I no longer could. I lied. Was easily devastated--unstable, really. I gave the phantoms free rein to my psyche and fomented the fantasy, nurtured it. I ruminated, lying awake at night, or in daydreams. This panic resurfaced through my thirties. It was a whisper, a voice, maybe male. An auditory hallucination? A memory from within my mother's womb?

My father left suddenly for a year in northern Thailand with Air Force Intelligence Operations. It was the height of the Vietnam War and of my junior-year misery in the all-girls academy. Mom, exasperated by my whining and pleading, transferred me to public high. To be sure, she'd made innumerable independent decisions about the care of us two adopted daughters, but not about school changes.

Dad faced the fallout of my move when he returned to New Jersey, his angst and disillusionment with the war compounded by my confused choice and behavior. I witnessed him break into tears, but as before, it wasn’t pity I felt, but embarrassment. He didn’t attend my graduation and withdrew even more from me. He retired as a Lt. Colonel and returned to work in New York City with the C.I.A. The worst time of my life was well on the way, as I imagine it was for them. My depression, sneaking, lies, alcohol, and street drugs took their toll on us, and his moody, stern presence exacerbated my angst. I left home at eighteen for marriage and young motherhood.

I had been spinning farther from the life my husband and I hoped for. We both wanted to pursue our education, and he was on track to his Ph.D. I took courses and worked menial jobs in a childcare home in Albany, and in the Career Counseling office at Columbia University, while we made do; caring for our daughter below the poverty level.

When my parents sold the family home in 1975 and left with Nana and my sister for a new life in California, I crashed, leaving our daughter with my husband and his parents in New Jersey. I worked in a county community action program for thirteen months, living with new friends. The medical assisting program I enrolled in balanced me a bit, and I divorced my husband, with mutual custody of our six-year-old. This couldn’t have been more devastating for us.

I can't lay all the fault for the wilderness in my brain on my father's career. Looking back, I believe relinquishment and generational trauma, abandonment, and separation triggered my turmoil.

To be continued.

© copyright Mary Ellen Gambutti 2023.