Hi friends and readers, I have a coming-of-age memory sequence for you this weekend. If you'd like to ensure you receive my weeklies, please subscribe.

1. A Faithful Crone

My adoptive dad and his sister, my aunt Rosemary, took me to visit their father's sister in a Manhattan convent nursing home. At the top step, Dad buzzed at the heavy wooden door, and a pleasant nun opened, greeting us with “Kate is expecting you,” and we followed her up a narrow flight of stairs to a hall of side-by-side doors. She tapped on one, speaking through it, “Your guests are here, Kate.” After a pause, the doorknob seemed to turn with effort. A small, ancient woman smiled in the half-open doorway. Her eyes were clouded, and her voice was a whisper, “Come in, come in!” An old-fashioned, black shirtwaist dress hung from her frail frame, draping over a dowager’s hump. Straggles of silver-blonde hair had fallen loose from the pins of her bun — we had interrupted her nap. The cane she leaned on was polished, yet rough — a tree limb — Dad called it a blackthorn shillelagh. Her thimble-sized room offered visitors a straight-back chair, or the single bed. She motioned to the chair, and I sat on her bed next to her, while Aunt Rosemary and Dad stood in front of the plain dresser. They chatted cheerfully, inquiring about Aunt Kate's health, updating her on the family’s news. She turned to me, and with an Irish-English brogue said, “Let me see what I have for you.” Her wrinkled fingers felt in the nightstand drawer for whatever she might find to give her adopted four-year-old grandniece, withdrawing her hand with a cluster of holy cards; souvenirs from the wakes of family and friends, a “miraculous medal” of the Virgin Mary, and a spare set of black rosary beads. Kate, the last of the eldest Caffreys, bequeathed a few tokens of faith to me, her nephew’s shadow child. I kept these treasures in my cigar box.

2. Reckoning

At the dawn of my reverence, I stand on the church kneeler and study a tint on the cover of a glossy white prayerbook, the image of a kind-looking man wearing a long white dress, sitting on a boulder under a tree, children clambering onto his lap. His soft, light brown hair falls to his shoulders, like mine does, at three years old. Distracted, fidgeting, I whisper loudly to my grandmother and mother, and I find that my babyish misbehavior comes with a price. I forget my transgression by the time we’re home, but my father reminds me, and his threat hangs in the air waiting, while he goes upstairs to change. All the while, my dread builds. My Nana’s room is next to mine, and I moan to her, “I won’t let him hurt me!” But she doesn’t save me. He has me over his knee on my bed, pushes my organdy dress aside, and the shame of his sharp slaps stings. I am indignant. “S-T-O-P!” Not yet ready to practice self-control, instead I taste bitter injustice. And so, the rituals of right and wrong, reckoning, and questioning begin.

3. Beginnings

Sister Mary tells the first-grade class we are at the age of reason and have something called a conscience. If we lie or take things that don’t belong to us, we may be caught and punished by our parents, and the man who made us. A child of six doesn’t grasp lasting retribution. We learn a creation story in the Baltimore Catechism and recite by rote calling out loud the answers in unison: Who made you? God made me. Why did God make you? God made me to show his goodness … Sister says that reason was the beginning of mankind’s troubles. My parents told me a story that I came from a place where there was no mother, and they took me home because I had no one. The mother I have took care of me instead of one who died, or didn’t want me. Reason, I think, is the apple that first mother Eve bit and gave to Adam. If we hadn’t been baptized, Sister tells us, we would have gone to Limbo, a cold place with no beauty or love, where babies don’t grow. Why did my mother leave me? I always want reasons.

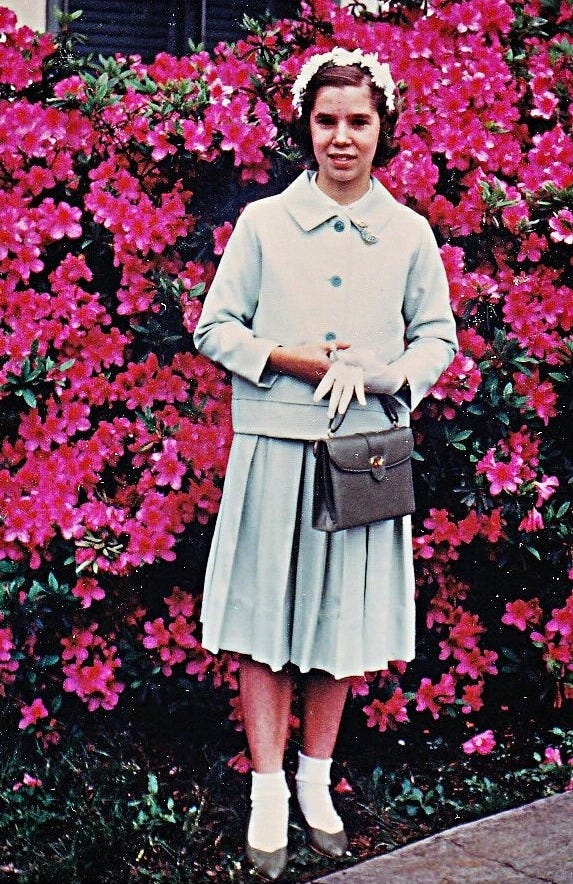

4. The First

On a warm, sunny Texas May 1957 Sunday, and Mom fastens a fine chain with a tiny gold cross pendant at the back of my neck. My white clutch pocketbook holds a new prayer book with a blue-cloaked Mary on its glossy cover, crystal rosary beads in a white brocade pouch Mom sewed, and a white embroidery-edged hanky. Dad takes portraits of his first communicant. My puffy white dress falls over a crinoline slip, and I wear sheer white anklets, pristine patent-leather shoes, and white lace gloves. A white nylon mesh veil drapes behind me to my waist; the frill-covered plastic crown is embedded in my short brown curls.

Our communion class has rehearsed, memorized, and fasted, the choir and congregation sing, “Come Holy Ghost.” A line of bride doll girls on the left, and on the right a line of boys in bowties and little jackets, hands pressed together—our fingers forming steeples to point heavenward—we process down the aisle to the first pews, where we fidget with our rosary beads and veils until Sister motions. Kneeling at the rail, my stomach tenses the moment Father’s gold robes rustle as he bends toward me with a gold chalice. I can’t understand what he says when he places the hard, tasteless host on my tongue. I hold the wafer away from my teeth, as we’ve been instructed, and mull the bland disc around my cheeks. I can’t discern the form of the mold’s impression I trace with the tip of my tongue. I swallow when it softens, digest the dogma. Many persevere in their devotion and hope to have one final taste.

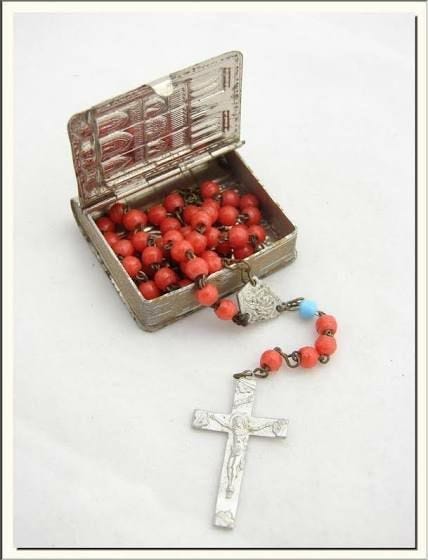

5. Souvenir of Faith

Sparkling, silvery, it fits in my palm -- the souvenir of Notre Dame Cathedral is from Dad. He's been away three months in Paris while I'm in second grade in a new school. As an Air Force officer and devout Catholic, he means to nurture my faith while we move from place to place, even while he's away. The tiny tin bible is bound and hinged like a locket. I trace my index fingertip across the cathedral spire-in-relief, the towers, buttresses, and high rose window. I pinch the tiny latch to release an orange glass rosary that ripples onto my fingers.

Fans oscillate along the side aisles and down the nave of Saint Frances Cabrini church during a Louisiana schoolday morning mass. Two girls sandwich me in a pew — curious? envious? — of my cathedral rosary case. They press against me, and might just pop me like a booster from their pew. I'm a new girl, again, and I don’t know their names, but I hold my space defiantly. I can’t stand the swelter, the heat of competition waged in the pew. How long before this souvenir is lost; this gift of faith?

6. Miracles and Wonder

The cigar box in which I kept my collection of religious articles was open with its contents on the bedside rug. The corpus of the pink plastic phosphorescent crucifix, one of my favorite devotional objects, recharged in the daylight, glowed green at night, or under the dust ruffle. To my surprise, it jumped over the spilled items, and I called out, “Mom, it moved itself! My cross flew! She expressed no doubt.

7. Spirit Down to Bone

I was eight when the base chaplain stopped by our home in the officers’ development to bless our three-month-old adopted baby girl. As he was leaving, he put a holy card in my hand, of a haloed, dark-skinned man wearing a long white gown and a brown robe. The card was stapled to a cellophane packet. “Blessed Martin De Porres lived hundreds of years ago in Peru. He was devoted to the poor. This is a relic: Ask him to pray for you,” Father instructed. Thanking him, I read the little label: Linen touched to the bone of Blessed Martin. How strange was this object of devotion! I imagined Martin’s white bones; his skeletal leg. Would it be a sacrilege to touch a relic? After a day or two, deciding, by the right of ownership, to view it closely, I detached the card, slid open the clear cellophane, and pinched the fine-woven waxy linen to remove it, held it this way and that to examine it. Then, satisfied with its mystery, I tucked it back into its protective cellophane and returned it to my cigar box of religious articles.

8. Devotion

Most evenings, Dad led Mom and me in the rosary. In front of the blue-and-green plaid sofa, I shifted my weight from my left knee, which was bandaged following a bicycle spill. “Offer it up for the souls in purgatory,” Dad admonished when I whined. The three-foot-tall plaster Infant Jesus who hovered on the end table wore silk, satin, and velvet, one of several robes my mother sewed for him.

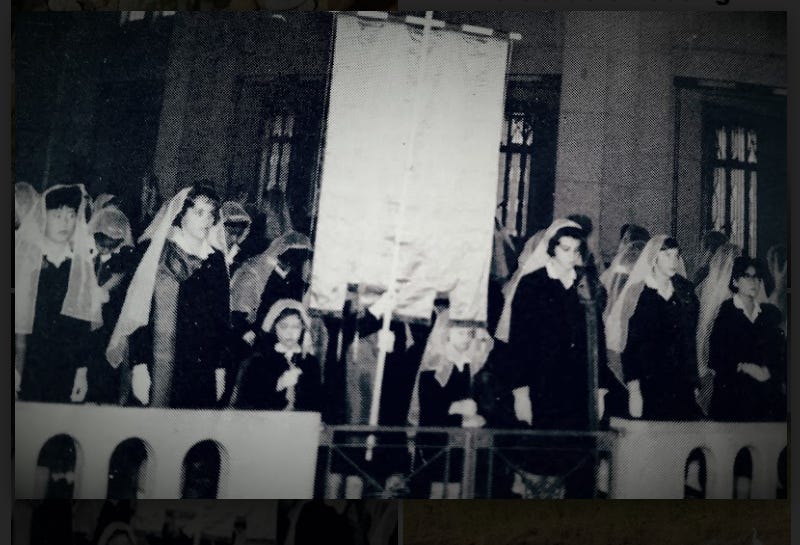

9. Encounter

White mesh veils on a wide windowsill in the study hall were for the sixth grade, the eldest class in Junior School, to visit the chapel of our International School. In our soft indoor loafers, we shuffled piously through the upper convent halls, into the chapel, a few of us exploring the choir loft to overlook the pews, the altar, and statues, and to admire the gold ornamented, vaulted ceiling. One afternoon, we turned a corner to encounter a nun kneeling in the middle of the corridor. Her eyes closed, she prostrated herself on the tile. Shocked by her appearance, we turned and bolted, chattering all the way back to study hall, slipped through the rear door, and returned our veils to the windowsill, sure we’d be in trouble if Reverend Mother learned what we witnessed.

10. Saints and Sinners

During our second summer in Tokyo, I rode my bicycle to daily Mass at the Washington Heights chapel and visited the pocket-sized library at the back for stories of mystics and young, holy women who witnessed miracles, like St. Bernadette and St. Teresa, “The Little Flower.” Her sweet sensitivity and her sickness intrigued me. Teresa was a Carmelite, and I imagined the gummy, tan candy cubes wrapped in cellophane. Young People’s Lives of the Saints showed her lying perfectly flat on her back in the convent bed. I read that Maria Goretti was stabbed to death at my age, eleven, by a boy cousin. I didn’t know what rape means, but I admired her for fighting him. Girls and women must be vulnerable, and weak. My father is religious and sometimes hits me with his belt. I see that faith didn’t save these girls from harm, even by men they knew. Dad more than once said he could kill me, and I have begun to hate him. Once he yelled, “Go to your room with no dinner! Only bread and water!” I’d been taught that God punishes sin and forgives us if we are sorry, but he never says he forgives me, nor that he is sorry, only I must apologize. Dad left the Catholic Juniorate Seminary when he decided to marry Mom in the 1940s, but remains adhered to the Church. Looking back, I believe he kept his religious life on the back burner, should his family life fall apart. After all, I was adopted -- he had “no children of his own.” He threatened to leave for a monastery, implying that by good behavior and attitude, I could keep him home. But he was frequently away on military service. “Don't push me, priesthood is my backup plan,” he might have meant. After he retired from the Air Force, he was ordained a Deacon, remaining in service to the Church for life, effectively giving up his adoptive fatherhood.

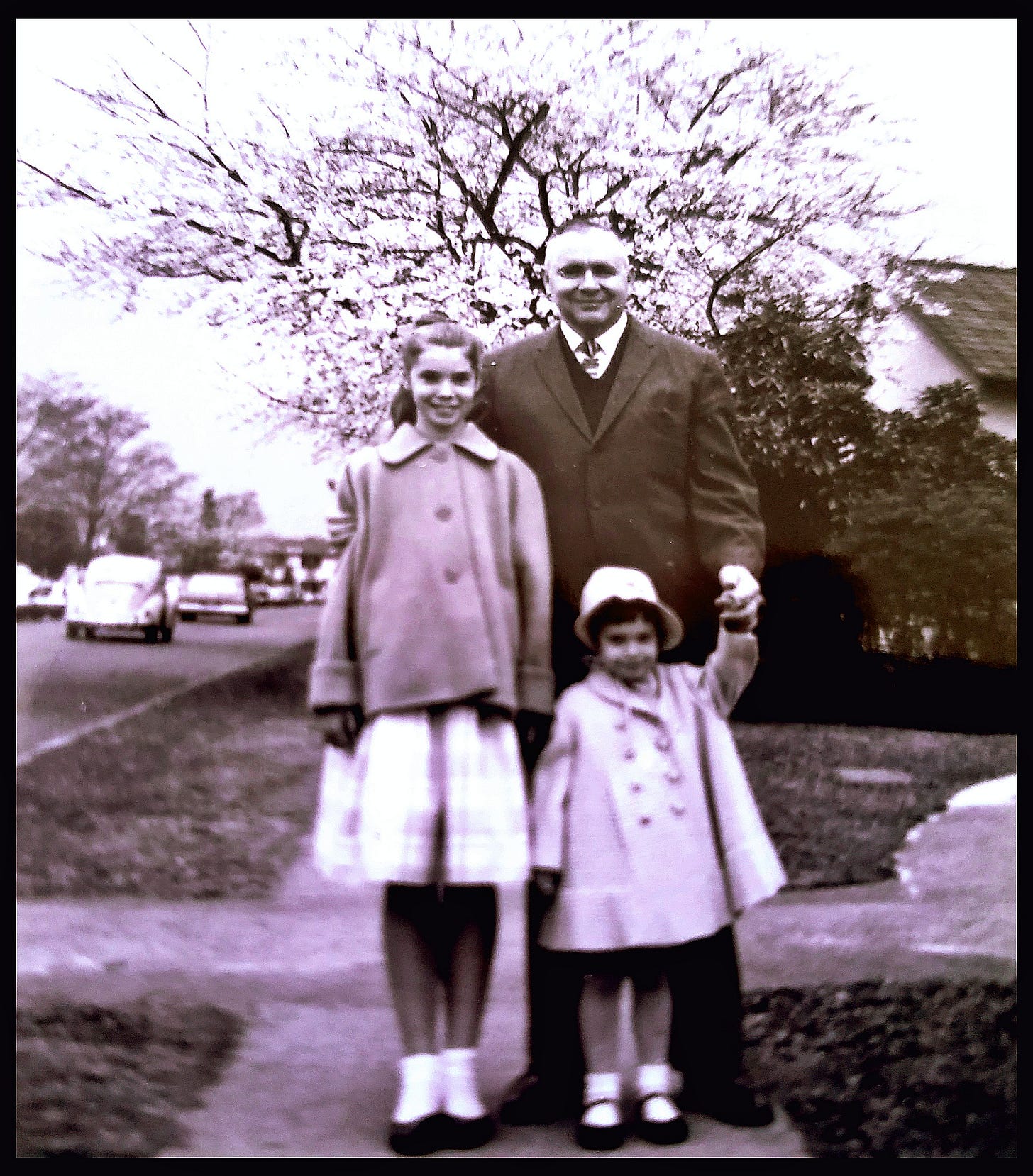

Sakura edged the sidewalk in our Washington Heights military housing community, the puffy pink cherry blossoms lighting our way to mass, on Easter Sunday, 1963, our second spring in Tokyo. Maybe he wasn’t satisfied with my report card grades, or my character development scores had slipped. He lectured me every day he was home, this time informing me how his career depends on his strong character scores — “I always get top reports. That’s why I get promoted” — and that my character reflected on him, which affected his advancement.

Mom sewed my Easter suit, a dirndl box-pleat skirt and tailored jacket in mint green and white check. She pinned a rhinestone-jeweled duck on the lapel. To complete the look: handmade silk cocoon shoes Dad brought home from temporary duty in Southeast Asia, slip-ons for me and pumps for Mom; a matching clutch for me, a pocketbook for Mom. But he banned my special outfit as punishment for the unsatisfactory report. Mom didn’t protest, although she must have been disappointed for her wasted efforts. He piled on my punishments: “Do not speak to me.” No bicycle riding, no playing dolls with my friend, Kathy (at her house — she never came to ours, although she lived close by). Why does he want me to feel loss? Mom put out an ordinary shirtwaist dress and my usual Sunday shoes. I forced a smile for the obligatory Easter photos for the family back in the States, masking my intense dislike and resentment for my adoptive dad. He allowed me to wear my Easter outfit the next Sunday, but I didn’t feel absolved — it was a new punishment, a reminder of my sins, and added insult to injury.

This made me sad. My adoptive father also a devout Catholic was harsh with me too. He demanded perfection in school, my chores and obedience. My mom did not stand up to him either. Eventually, I did.

Mary Ellen Gambutti: My daughter and my son-in-law are loving parents of two boys and adoptive parents of a wonderful girl, then 8-months, now 17-years, from Hunan (in China).

She is well loved by all, including us grandparents.

We have a long-departed friend, who passed away at about 70 years of age, who was adopted and well-loved.

I don't understand the cruelty of your adoptive father at all.

As a devoted Catholic myself, who grew up under Pius XII and the Baltimore Catechism, I have never identified with the authoritarian, but rather with the Jesuit and meditational tradition.

I am very sorry indeed you grew up with sanctimonious, weak persons.

Thank you for sharing so deeply of yourself.