Dear Readers, I hope you’ll enjoy my lyric essay.

A Memory Sequence: Tokyo, 1961-1964

In navy blue jumpers and jackets, several of us waited for the school bus in the parking lot of the non-denominational chapel. The bus shuttled us to the International School of the Sacred Heart. I turned ten in the fall of 1961 and rode with other Catholic daughters of Air Force servicemen through the end of the 1963 school term. The U.S.—occupied land was then returned to the Japanese people, and Washington Heights military-dependent housing was demolished; set to be the site of the 1964 Summer Olympics. It has since been restored to Yoyogi Park.

On the last day of school, forgetting to change from my soft-soled, blue loafers into my brown loafers, I wore the inside shoes home on the bus, leaving my brown shoes in my cubby. My mother was annoyed that I'd left them in school, only noticing a few days later that I'd come home without them. She might have been anxious because my dad was away overseas. She ordered, “Go get them!” I didn’t protest walking alone in downtown Tokyo, a ten-year-old girl who spoke only English. I didn’t wonder. I hurried off.

Kathy and I hit it off when we met at the school bus stop, and she invited me to her house in a quadruplex court, like ours, across the street. She was a year ahead of me in sixth and seventh grades at Sacred Heart. She was ladylike, big-sisterly, with a sense of humor, and she introduced me to dollhouse play. We collected furnishings, and various dolls, staging settings in her American-style suburban colonial cross-sectioned dollhouse upstairs.

An obedient daughter, I set out on my solo trek, the consequences of my carelessness and Mom’s impulsivity, wearing cotton shorts, a shirt, and blue Keds. I wasn’t wearing my wristwatch, and I didn’t have my dependent I.D. card. I ventured to guess the school bus route. I wouldn't know until many years later, that I had been abandoned by my natural mother at birth, and I cultivated separation anxiety.

“Are you wearing your watch?” my mother often asked, as I left for Kathy's house. “Be home by five.” That gave me an hour to play. Friends rarely came to our house. Mom didn’t encourage visitors, and sleepovers with friends were out of the question.

At the main gate, I waved to the Japanese guard. I walked past the Meiji Shrine entrance; its tori gate rising into the trees, past the Harajuku train station, the businessmen, the kimono-clad and western-attired shoppers, and Japanese students in uniforms — their classes not over. In the gleaming business district, I leaned against a storefront at the Shibuya intersection, then crossed with the crowd. On the hill, the narrow busy street, I turned right and walked under the tori gate into the Sacred Heart campus. The empty driveway and play yards were strangely still. I hurried past the stone lantern and wood-framed tea house, to the white, multi-level school building, bounding up the wide, marble steps, my pigtails flopping at my back. A few familiar nuns floated in the corridor, greeting me with nods. In the quiet cloakroom, I was relieved to see my brown shoes had waited, and I pulled the culprits from my cubby. A quick stop for the restroom and back down the steps to the drive, a bend right and under the tori. I faced left. The day was getting hot, and I was tired. Something changed. I must have wandered. I must have disappeared into myself.

Kathy's parents weren't as rigid as mine. They knew my toddler sister and I were adopted. Kathy knew I dreaded going home, and I began to reverse the minutes on my watch at a quarter to five. I wanted to cheat the time, to help myself to a few more moments, absorbed in the peaceful pleasures of imagination and friendship. To delay the inevitable. A problematic report card meant punishment when Dad came home from the office. Once, he wouldn't let me eat at the table and Mom brought me bread and water to my upstairs bedroom. My restrictions and denials included no talking until he released me to speak. His threats, his insistence on table etiquette, his concern for appearances, the proper placement of utensils, how the bread was to be cut before buttering and eating a slice, and his disciplined approach to duty as a military man and adoptive parent made for stressful evenings when he was home.

Kathy, I was relieved to see you both that sun-seared late June afternoon in front of the Oriental Bazaar. Your mother asked with a frown, “Who is with you? Are you alone?” Realizing it was odd, I blurted out, “My mother made me go to school for my shoes!” I succumbed to tiredness and self-pity; confused about how I got there. My loafers were heavy and hot in my arms. Your mother dispensed a small bottle of Pepsi from the machine outside the shop and opened it, handing it to me. “Take a drink.” It was the coldest soda I'd ever tasted. “Come home with us — here’s the car.” I was happy to clamber into the back seat of your Olds.

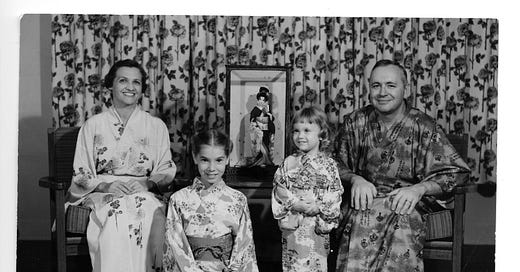

On Saturdays, Dad sometimes enjoyed shopping in the Base Exchange or would drive us to Harajuku in Shibuya, the shopping district outside the gates, into the crowded streets and alleys. Traditional and popular Japanese music wafted from the shops and transistors, voices in the language my family couldn’t comprehend, except for a handful of words and phrases; the advertising art with kanji characters I never learned to read. In the Oriental Bazaar, a souvenir palace with an unfortunate name, and accessible Far Eastern culture and kitsch, my family Iingered at the displays, the shelves heavy with dolls, toys, ceramics, clothing, and furniture. Mom chose a graceful geisha doll in a kimono, poised in a wood-framed glass case, a floral fan in her hand, picked out an earthenware incense burner, and a Satsuma multi-floral trinket box, and lazy-Susan set of the same pattern. With my spending money, I bought a few tiny glass animals, and Dad could be persuaded to contribute a few extra yen for wooden-painted peg kokeshi dolls, a lucky red Daruma doll, a Hakata doll in folk dress, or twin Ichimatsu Gofu, jointed baby dolls made of eggshell-like plaster. These were the times I loved my dad — when he seemed to love me. I chose a few hard fruit candies wrapped in dissolving rice paper. Outside, the mingling fragrances of street food were soba noodles, fried dumplings, skewered chicken Yakitori, and savory grilled rice crackers. We sampled on the way to our Buick.

Fueled by Pepsi and my adventure, and relieved to be safe at home, I called to my mom, “I have them! Kathy's mom drove me home from the shop!” My mother didn't ask for the details of my journey. I wonder if she told my dad about it when he returned from his trip.

In Ueno Park -- two adopted sisters in home-sewn dresses