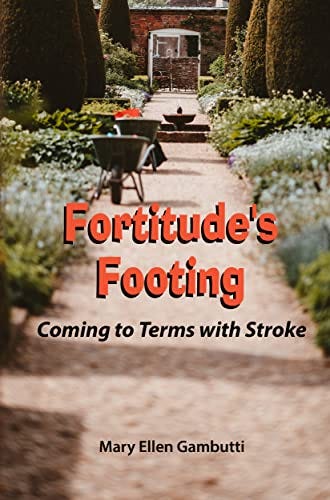

Dear readers, I have a few early March musings for you, versions of pieces from a small memoir with a big story, Fortitude’s Footing, about the hemorrhagic stroke I survived at fifty-seven. Thanks so much for reading and supporting my work with your follows and subscriptions. ~ Mel

One.

Bad Mountain Weather: Tanka

A fog of voices washes

over the cool, white bed

saying you're lucky,

ambulance delayed,

helicopter — survived

bad mountain weather.

¤

Weakened, I work to stay

alive in June-July-August

weeks lost in this

Summer of bad weather —

I heal

In this place of respite.

¤

Unfeeling, numb I work on my

brain and body

in the summer of

no birds and gardens

until the sky and mind clear

and sun sparkles.

¤

When the red and gold

fall slanting sun rays

breach the haven

where I wait, I'll find

the chilly stream of courage

and deeply drink.

¤

Laurel Ridge, Fayette County, Pennsylvania

Morgantown, West Virginia, June 2008

Easton, PA

(An earlier version was published in The Bamboo Hut)

Two.

Art of Language

Only in my mind can I talk, these neurons dash across the dark screen of my injured brain are the words I cannot form. Signals to my face, tongue, and mouth muscles are jammed. Held up. Can’t get through.

After my critical early weeks in Ruby Memorial Hospital's stroke center, two ambulance drivers working overtime transported me to Easton Pennsylvania Good Shepherd rehab center, where we’d be close to home. It was an exhausting ordeal, strapped onto the gurney; my right side, was a dead weight. Recovery from brain injury demands sleep and therapy, and speech, occupational, and physical therapies would continue for many months despite my preference for peace.

The speech therapist with shoulder-length blonde hair, wearing a white lab coat over business casual, pushed me through the rehab unit to the adjacent therapy department, ducked behind a blue curtain, positioning my “Geri-chair” against two matched wood furniture pieces, like a teacher’s desk and chair. Yes, I was in school, lacking star deportment, slumped toward my left with right-sided neglect, I was being retrained in the art of lost language. The therapist’s insistent voice, her attempt at a cheerful demeanor, her large, percussive laughter, and her large expectations of me, further frayed my fraught mind.

Without delay — there was much to be accomplished — she flashed picture cards in my somewhat diminished field of vision; my glasses had been lost during the crisis. “What’s this?” I struggled with the elementary scenes, characters, and objects, and her drill continued. “Tell me what you see.” I could see, and knew what I saw: Mother in a dress and apron at the kitchen sink. Mom works in the kitchen. Children play in the yard. “What are the children doing that’s odd?” I’m the child that can’t tell her. "What doesn’t belong here? What does she see outside the kitchen window? Say what’s wrong with the picture.” Everything was wrong with the picture, including myself.

Words didn't loosen on my tongue, and the voice I produced was alien. My auditory perception had improved in the first days after the brain hemorrhage. But weeks later, I was still dismayed, fearful I might not speak intelligibly again. I understood the stroke had injured my motor center for speech; a defect of the neural connection between my mouth muscles and my brain caused Apraxia, which is tied to cognition. Aphasia is a problem of word-finding common in stroke patients. I was affected by both conditions. I couldn’t read, tell time, or make sense. When the dietician in Good Shepherd called my bedside phone to take my dinner order, I knew what she was asking, and I was confident in my answer. But she pressed me for details, and I realized I wasn't making sense, and hung up. She was used to it, I imagine, and sent me chicken tenders every night, so I could eat without a fork and not have to speak on the phone. Normal phone conversation overwhelmed me for a couple of years.

My frustration — at times, internal rage — was crippling. My painful awareness that my speech was unclear and incorrect caused me, more than once, to break down in tears. I couldn’t remember the words, and when I did, my efforts embarrassed me. I feared that my clear enunciation was in the past.

Interpreting the story cards led to reading comprehension. I needed to re-learn the art of language and I embraced speech as though it were a new skill. The challenges put to me would become more complex during the three weeks on and week off cycle of outpatient speech, occupational, and physical therapy.

By the fourth year after my stroke, I was speaking normally, with only occasional word slippage, misfires, and malapropisms, which my husband seems to find amusing, even endearing. The writing classes I took through the community college were the threshold to recovery. I honed the basic skills I’d lost to brain damage: comprehension, word choice, usage, and sentence structure. Courses in memoirs and personal essays have helped immeasurably in the recovery of memory, reflection, imagery, description — even emotional regulation.

Several weeks into rehabilitation, the director, an occupational therapist, explained neuroplasticity — Oxford Living Dictionary: “The ability of the brain to form and reorganize synaptic connections, especially in response to learning or experience or following injury. He said the tendency for the brain to change and heal with activity and repetition may give hope to brain trauma survivors. But there is no escaping the work required for the neuromuscular system to return to strength after its collapse.

“Hemorrhagic stroke can cause sudden death, or there is a good chance at recovery if you are willing to do the work.” I recalled hearing something like that just days after my admission to the stroke center in West Virginia. I had the will and determination, and the strength. Curiosity worked in my favor — I was open to the path of learning.

Three.

Now, Be the Dance

I am a blanket pulled noiselessly through the water’s warm surface. In a stream, with firm hands, she guides me in the Watsu dance. On my back, I’m moved in slow motion to the left, then right. My eyes are closed, and I lose direction. No obstacle, no hesitation, or effort. No need to try.

“Trust is the key,” I hear Patti say as I float freely, my silver tresses streaming in silent water. She pivots and turns, and in her hands, I feel an easy stretch. “Now, be the dance,” she says. I do nothing to resist her gentle strength. In quiet, I feel a stirring. Time, determination, and work have healed my injured brain. I’ve fought against the evil of my flaccid side. Now, at this moment, I allow myself peace, and an end to work. In this pool, I feel joy in the suspension of time and place. No need to try.

Happiness is transitory contentment, a state of sensory pleasure. But, we may pass through that gate into a more glorious garden. J.K. Rowling’s character, Albus Dumbledore, said, “Happiness can be found even in the darkest times if one only remembers to turn on the light.” The light that came on for me saved my life: the understanding that all is lost if we allow it to slip away.

The stroke threatened to take me away from myself, but it did not succeed. It seems simple now: my toes, then my foot moved. Kahlil Gibran writes in The Prophet that emptiness is first needed to live fully. Both sorrow and joy are necessary to live a balanced life. My emptiness turned to joy.

We must remember to switch on the light–our conduit to joy. Call it inspiration, happiness, contentment, engagement in art, creative flow, song and rhythm, natural beauty, and the meaningful written word. The light is a channel, the way to a state of mind that is joy. It is beyond time and place. It is a religious experience, salvation, or enlightenment. Joy is ecstasy, it is bliss. Joy is wholeness in being, the full measure of self, and oneness. Beyond our physical woes, lies a place where we may rest body and mind in well-deserved contentment. Joy is the calm blessing that can bring tears. I’ve returned to self-expression. When there is no need to try, then we may feel joy. We are the dance.

They were crucial in explaining what had happened and made me feel less alone.

your writing always touches my emotions,you truly have a gift